The SJs over at The Jesuit Post posed a question on Twitter a few days ago: What do you think about public confession? Naturally, I had lots of opinions, since that was the major focus of my masters’ thesis. As it turned out, they were talking about Lance Armstrong, not the practice of confession in the early Church. But I’ll still offer an answer.

Public confession was the norm when a need first developed for a second forgiveness of sins (the first, of course, came from one’s baptism).

In the era of persecution, the sin for which Christians most frequently needed to be reconciled was apostasy. Since apostasy so explicitly damaged the community (as it was a renunciation of the principles of that community), and since it was the sin which prompted clarifications of the principles and practices of paenitentia secunda, reconciliation to the community (pax cum ecclesia) became a priority.

Still with me?

As the practice of penance developed (and indeed, it was always a practice, not merely an attitude), this element of pax cum ecclesia remained the primary goal of one’s penitential acts, since membership in the Body of Christ was viewed as the only way to receive grace or to gain eternal salvation. Forgiveness of serious sins after baptism always included a public confession as one of many penitential acts. A contrite spirit was manifested in actions; ones penitence could not be kept interiorly.

Fast forward to Aquinas. Writing after the spread of private confession (thanks to the Celtic monastic practice, which assumed trained spiritual directors as confessors), our boy Tom identifies interior penitence, rather than reconciliation to the Church as the res et sacramentum (the symbolic reality) of penance. (If you are into this sort of thing, watch Rahner, who is Team Pax Cum Ecclesia, wrestle with this in Theological Reflections X).

We know how the rest of the story goes. The Council of Trent focuses on the power of the keys rather than the role of the Church community in reconciliation. Penance turns into a big honkin’ mess, with penitential manuals and buying indulgences and private confession in which neither the confessor nor the penitent has much spiritual training or guidance.

In their attempts to clarify the effects of the sacrament, here’s what the Vatican II Fathers had to say, which is later quoted in the Revised Rite of Penance (1974):

Those who approach the sacrament of Penance obtain pardon from God’s mercy for the offense committed against him, and are, at the same time, reconciled with the Church which they have wounded by their sins and which by charity, by example and by prayer labors for their conversion. – Lumen Gentium 11

*******************************

OK, the nerdy part of the post is over. So what do I think about public confession?

I don’t particularly want to do it myself, but I it speaks to public element of sin that we have forgotten.

You don’t need me to tell you that the modern west tends toward radical individualism. Everything is either purely interior (a quality which, as I mentioned, would have been unheard of in ancient times) or private between a person and God.

In the case of bad actions, this is patently ridiculous. Actions affect other individuals, and affect the community. When someone violates the trust of the community by doing something that damages its well being, we want to know that they know what they’ve done, and often we want to know why.

I think that’s why a mea culpa from someone as prominent as Lance Armstrong is so attractive and intriguing. We trust our celebrity demi-gods – in some ways, their public existence holds our society together as shared experience – and when they let us down public contrition is demanded of them.

God willing, every one of us is a bit of glue that holds together our smaller communities. We matter, and so do our actions. Even if we don’t want to shout our sins from the rooftops, we can’t imagine they are totally private. Contrition is not a magic trick, a switch we flip that makes everything right as soon as we feel the right things. What makes things right is repairing relationships, which is inherently public.

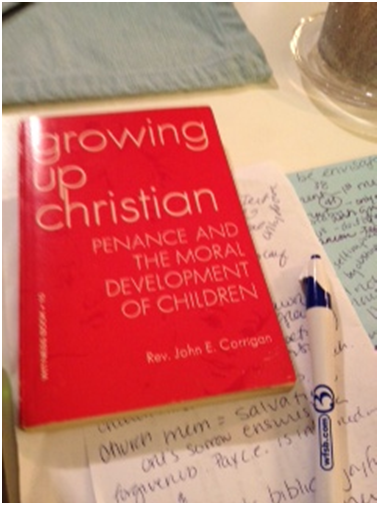

While researching my thesis I read thousands of pages about penance and reconciliation, and near the very end looked at a tiny handbook that had been in the basement on my mother’s bookshelf for as long as I could remember.

This book described penance in the early Church as “public, biblical, and joyful”. That was my Aha! moment. Only public acknowledgment of brokenness, in whatever form that takes, allows us the joy of reconciliation.

At its core, reconciliation is about community not only for theological reasons but because at our very cores relationship is what we seek and where we encounter God. So through this sacrament – and often in the ways we live out its principles in a secularized world – we ritualize and sanctify the healing of the wounds we have created between ourselves and others, and between ourselves and God.

What do YOU think about public confession?

Leave a Reply